I became self-employed on 1 June 1996, and I found myself with one consultancy contract. It was a training contract, to train the officers of a hydrography ship of the Indian Navy, about Unix and networking. These officers had been put in charge of a shipboard GIS system which ran on a SunOS workstation, and they were quite concerned that they didn’t know how to do basic things like clean up junk files, take data backups, etc. So, I pitched to them that I’d conduct perhaps a dozen lecture sessions for them on their ship, for a sum of Rs.9,000 plus taxes.

Lion Gate

So, twice or thrice a week, I would land up at the Lion Gate of the Naval Dockyard in South Bombay, from where, after a security check, a jeep would take me to the INS Investigator, berthed a kilometre away. I would board the ship to the tune of pipes, then walk up to the bridge, where some 8-10 officers would be waiting, in starched white uniform. I would use a flip-chart board and marker pens to explain the basic concepts of Unix, Ethernet, and TCP/IP networking to them. After one and a half hours of this, we would all walk down to the wardroom where I would be offered refreshments — a glass of chilled lime soda. After 15 minutes of banter and gossip, I would disembark from the ship, again to the tune of pipes, and a jeep would drop me to the Lion Gate.

Soon, the time came for me to raise an invoice on the ship, and the officers quietly let me know that it would be nice if my letterhead carried the name of a firm instead of a person — “looks more professional, you know…” I took the bit between my teeth and decided to create a proprietorship firm for myself. I called it SpaceNET, and immediately registered a domain name: spacenetindia.com. Then came the part of crafting a letterhead. That part threw up so many fascinating meanderings. It amazes me, the utter pointlessness of the small steps one walks through to reach God knows where, always with a sense of purpose but actually without the slightest clue.

Rain-lashed doorway

I carry a very vivid half-minute memory of me standing in a rain-lashed doorway. I have no idea why some snippets stick in one’s mind when nothing else does.

This was one of the days when I had emerged from Lion Gate and was walking somewhere, to catch a cab for some other meeting. So, I had walked towards Flora Fountain, almost certainly along Sir P M Road, when a squall hit, out of the blue. This is Bombay in the monsoons, what do you expect? I hurried to a doorway and stood there. All the buildings in the Fort area of Bombay are at least a hundred years old, and have large doorways. The door was shut, but there was place to stand back, pressing one’s back to the huge wooden door, and more or less keep out of the rain. I was wearing a formal Zodiac shirt and trousers, and my only pair of leather shoes. (Till just a few years back, I had just one pair of formal leather shoes — a black lace-up derby pair, full brogue work, wingtip toe. It is as if I didn’t know any other type of formal leather shoes.) I carried a tan leather briefcase — a very nice looking one. No suit or tie.

So, here I was, in that doorway, standing ramrod straight, back pressed to the old polished dark brown wood of the door, dimly aware of people scurrying to get out of the rain, while the heavens did their Bursting Out thing.

And I remember very vividly, the toofan-like emotions which ran through me. These were not thoughts, they were more like a picture. Utter desolation. Total incomprehension. Slight bitterness. Feeling totally lost and alone.

If I had to put these non-verbal images into words, I’ll say I was asking myself, “What the hell am I doing with my life?? Standing in that rain-lashed doorway??” Eyes smarting with the rawness of the moment.

When I think back at that half-minute memory, I know I felt no fear. Strange.

Then the rain subsided, and a hundred pedestrians stepped bravely out and walked their different ways. I remember glancing at my leather briefcase and concluding that it wasn’t too badly wet — a wipe would set it right.

This tiny episode was prescient. During my entrepreneurial journey, I’ve re-visited this same state of blank incomprehension and desolation every few years, and asked myself the same question. But none were as inchoate, as intense, as the first one.

Natural shade

I shared my wish to create a letterhead with the only person who I knew who had any experience in such arcane areas and the patience to chat with me about anything. This was Rameshchandra Sirkar, my friend’s father. Ramesh taught me almost everything I know about typography, page composition, printing (as in books), monotype and linotype machines, and so many other things. He introduced me to Hornblower and Lord Peter Wimsey, and was himself a fan of Modesty Blaise, Kumar Gandharva and about a hundred other things. We used to chat incessantly, and though we were aware of the difference in our years, the conversation never flagged. I taught him about TeX and LaTeX, and discussed Don Knuth’s work with the Computer Modern typeface. (He quickly disabused me of the greatness of Computer Modern, and I’ve stuck to Palatino, Garamond, or similar font families with my LaTeX ever since.)

He enthusiastically agreed with my idea of designing a simple letterhead. I showed him some proofs done with Microsoft Word and printed on my friend’s colour inkjet printer. We discussed which should be larger, the firm name “SpaceNET” or my name. He said, with the wisdom of his years, that if I wish my firm to one day be larger than me, then I had best keep the firm’s name more prominent. Prophetic words, and they struck a chord, so a bright red “SpaceNET” became the most prominent part of the letterhead.

He then asked me, “What sort of paper are you thinking of using for the letterhead?” I hadn’t a clue. So he continued, “The world has this strange fascination with executive bond, but I don’t know why they crave it. It’s unnecessarily expensive, a bit too showy. I feel good map litho, which is used for printing good books, will do perfectly.” I, who had no idea about map litho, nodded, waiting for more wisdom. He then said, “If you really want showy, you should go all the way and look for alabaster coated papers. These coated papers are exquisite, and the whiteness you get is something else.” And about map litho, he put in his final suggestion: “Don’t look for the bleached white everyone uses. Try natural shade.”

Natural shade, it turned out, was a kind of pale cream colour you get when the paper is manufactured without any bleaching or whitening agents. The resultant colour is so beautiful, so delicate, and dare I say, so natural, that I fell in love with it. The only thing which remained was to decide the weight in “gsm” (grams per square metre). Ramesh’s advice: for good letterheads, don’t make it too heavy, try 100 gsm.

So, off I went to the bylanes beside VT station to buy map litho, natural shade, 100 gsm. In those bylanes, wholesale paper traders would sell you “teyiss chhattis ka sheets“. In other words, sheets of twenty-three inches by thirty-six inches. Using such sheets, one could cut eight sheets of US letter-sized letterhead, but I had become a metric-system nazi by that time, and nothing short of precise A4 would do. So, one gets to carve out seven A4 sheets from one sheet of “teyiss-chhattis”.

So the drill was to buy, say, 20 sheets of map litho natural shade 100 gsm in the teyiss chhattis size, then carry the bundle to the cutting shop in the next lane. This cutting shop would ask me what size I wanted, and would then proceed to cut precise 210 x 297mm for my A4 pages. They would tie these into a fresh bundle, and I’d carry them back to my home, thirty-five kilometres away, by local train.

Ramesh also taught me to get rubber stamps made in my firm’s name (“Get these self-inking stamps, they cost a bit more but then you don’t need a stamp pad, saves you the mess.”) and visiting cards (again in natural shade, but 250 gsm, and in a beautiful handmade texture, then screen printed).

Those paper merchants still run their business in Modi Street and other bylanes beside VT station today. Our company used map litho natural shade for several years, and then slowly the company grew, and others began taking decisions and moved to white stationery. Our lives lost a bit of colour.

Book-keeping

I had no business background at all. I had two friends, Hareesh and Sanjay, with whom I did occasional joint projects, conducting workshops (“Internet Express” at the Indian Merchants’ Chamber), setting up websites, etc. I was the techie one, they had the business brains. I marvelled at the way they handled clients, pitched services, conducted small talk so smoothly, built relationships, followed up on leads. I had absolutely none of those abilities.

Hareesh taught me the basics of accounting. He literally made me sit down with a notebook and a pen and wrote things for me, explained to me the idea of debit and credit, explained asset accounts versus expense accounts, and the whole idea of a balance sheet. He explained how one’s income and expenses go into an Income and Expense Statement, and the closing balance goes into the balance sheet. He explained that when a client gives me an advance, it’s not income — it’s a liability. It’s a balance sheet item. When I buy a computer, it’s not an expense — it’s an asset.

He spoke in a soft voice, used precise statements, and developed concepts step by step. He must have thought me a complete and utter idiot, because he was teaching me stuff which he must have learned from his family when he was in middle school, not even high school. But he taught this idiot carefully, and that learning has certainly been a long-term balance sheet item for me.

Even today, I find that my basic accounting concepts are clearer than many professional business heads of large organisations. I know less of the rules and conventions than professional accountants, but I seem able to hold my own when it comes to concepts. I still owe Hareesh.

Kishan

Kishan had worked with me in my previous job, and was one of the smartest programmers I had worked with. He was thinking of getting out of our previous company too, so in October 1996, he joined me. My training programme with the Navy had come to an end, and we then got two consultancy contracts with two giants, consulting with their IT teams. These were Reliance Industries and ICICI.

Reliance had their headquarters in Maker Chambers IV in Nariman Point, and ICICI was a long walk away, in Backbay Reclamation. Nariman Point was at that time the glamorous and happening hub of business and corporate life, and everyone who was anyone would be meeting others there. We worked with Reliance at a time when TCP/IP networking itself was a novelty, and Novell Netware and Microsoft LAN protocols were common. We helped Reliance set up a handcrafted firewall using a Linux box, and worked with the IT team of ICICI to build an Intranet. They wanted to set up a policy database on their Intranet for general access by all the loans and project assessment teams.

Kishan and I had no office. We would travel by local train from our homes to our clients to work in their offices. On many days, I would spend half a day at ICICI and walk down to Reliance for the other half. The cultural differences between the two organisations would make my head spin.

Kishan and I soon realised that it would be a good idea to print a good-looking business address on our visiting cards, so we contacted a posh business centre in Nariman Point, called DBS Business Centre, and signed up for a mail-messaging plan. This means that they would receive mail for us (yes, snail mail) and call us up that we had mail. They would also receive phone calls for us, tell the caller that we were not in, and would take a message for us. Cellphones had just entered the country, and we couldn’t afford them. Neither could we afford laptops. Typical laptops at that time would weigh four kilograms.

This is how two clueless young men, without an office, began working hard, billing for our time, and helping giants of the corporate world of Bombay build essential pieces of their IT strategy.

A computer appears

Kishan and I didn’t have a computer — no money. A friend, JD, lent me Rs.50,000. He was working in the US, and had more money than I. The entire amount went into the following assets:

- A computer: unbranded, assembled beige box: Rs.26,000

- A ZyXEL U1496E modem: supports data, fax, and voice: Rs.10,000

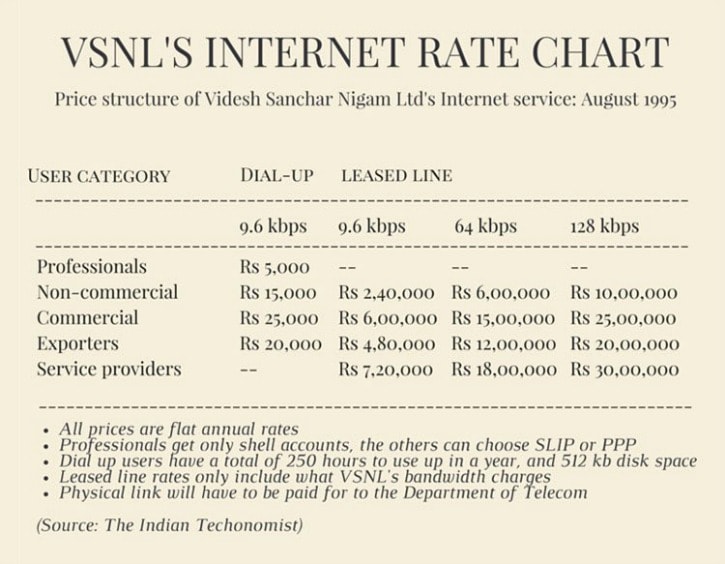

- The fees for an Internet connection with VSNL: Rs.5,000

I don’t remember how much RAM my computer had — probably 2 MB or 4 MB? With the computer came email. I ran Linux on the computer — of course.

This article from News18 is a good reminder of the Internet access tariffs we faced:

As money started coming in, I upgraded my account to “a TCP/IP account”, which meant that my computer now got a proper IP address and could push out mails over SMTP, pull in mails over POP3, and I could run a browser on my computer and it would connect worldwide over HTTP/HTTPS. A “shell account” meant that you connected using a terminal emulator and got a black screen on VSNL’s servers, where you could use Lynx for browsing and some text-mode mail client to handle emails, but couldn’t do almost anything else.

NCFM

The NSE heard about us, thanks to our work with IndiaWorld (whose acquisition by Satyam Infoway had hit even the Wall Street Journal as the largest acquisition deal in the dot-com space outside the US till that date). In fact, even ICICI and Reliance had heard about us thanks to our work with IndiaWorld.

The NSE said that new SEBI guidelines required all stock exchanges to conduct an exam on derivatives, and only broking houses who had at least two certified brokers who had cleared this exam would be allowed to trade in derivatives. Derivatives were a brand-new idea in India. The NSE had decided to be path-breaking and revolutionary, and design an examination system which would not have any paper. It would be taken by candidates sitting at browser terminals, and each examinee would see a different question paper. Could we build the system for them? Needless to say, they also had a tight budget, else they would have given the contract to one of the software services giants who were always circling them, within hailing distance.

So, we started work on NCFM, the NSE Certification in Financial Markets. It an examination system, with question banks, question paper planning, admit card management, money management for fees, and everything else. We joked that it was turning out to be an ERP for examinations.

We built it to be totally DBMS-agnostic, and wrote the code in Perl/CGI, with almost no Javascript. (Javascript was not even very stable at that time; we didn’t trust it.) We used no stored procedures or triggers, and we demonstrated the cleanness of our code by building it on Linux and MySQL initially and then migrating it to Solaris and Oracle in a matter of days.

The NSE used our system in production for 7-8 years, issuing more than 30,000 certificates, till they got it re-written in Java by one of the software services giants one day.

But our team was overloaded — we needed to grow.

Hemanand and Raghu

In April 1997 or thereabouts, we thought we had too much work on our hands, setting up file servers and email servers in small and large offices. We were still not doing actual application software development, but we already were swamped. We decided to hire two young engineers.

We advertised in the classifieds section of the Times of India, asking applications to walk in for an interview on a given date. We booked a room in a business centre called Key Business Centre at Nariman Point, prepared a multiple-choice C programming test, and waited. Several dozen applicants walked in, took the test, and left. Raghu and Hemanand stayed behind; they had done splendidly. We chatted, and soon enough, we asked them to join.

Hemanand had heard about our tiny firm from his friend, my brother. Raghu had been working somewhere in a hardware support firm and had just walked in by seeing our ad. They joined, and we became a merry band of four young men.

We still didn’t have an office. We travelled straight from our homes to our client sites and worked there all day. We would catch up on the phone at night, and even that was not a daily affair, given our long commutes. So we decided on a ritual to stay together — we used to have one dinner every week, typically on Friday nights, at an expensive restaurant in South Bombay. The restaurant was the Rangoli, in the NCPA. Like so many things of South Bombay, Rangoli does not exist. I remember that the four of us would laugh and crack the weirdest jokes, teasing and imitating each other, cracking jokes at the expense of our clients, and mock-lamenting our misfortunes. That laughter washed away the madness of serving crazy clients all week. The dinner bill, I remember, would be roughly Rs.1,000 for the four of us, for a full meal without drinks. We never drank in those days.

Kishan is a sought after senior technical consultant today — his name is known and revered in the financial services sector of Bombay. Raghu has been the CTO of a tech company for several years (the company just went public), and Hemanand lives on the US East Coast, leading a small team of equally senior hands-on techies, working for a financial services giant. We have all remained hard-core hands-on technical.

This is how the four of us ran our lives till about April 1998, when we grew from four to ten. That’s another story.

When I read the account today, the only thought which comes is that things happen. We live in the illusion that we do things, but in reality, things happen.

Leave a Reply